Scottish Music on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Stringed instruments have been known in Scotland from at least the

Stringed instruments have been known in Scotland from at least the

Pop and rock were slow to get started in Scotland and produced few bands of note in the 1950s or 1960s, though thanks to accolades by

Pop and rock were slow to get started in Scotland and produced few bands of note in the 1950s or 1960s, though thanks to accolades by  Scotland produced a few punk bands of note, such as

Scotland produced a few punk bands of note, such as  The late 1990s and 2000s saw Scottish guitar bands continue to achieve critical or commercial success, examples include

The late 1990s and 2000s saw Scottish guitar bands continue to achieve critical or commercial success, examples include

Stuart Eydmann: The Scottish Concertina

*Hardie, Alastair J. ''The Caledonian Companion – A Collection of Scottish Fiddle Music and Guide to its Performance''. 1992. The Hardie Press, Edinburgh. *Heywood, Pete and Colin Irwin. "From Strathspeys to Acid Croft". 2000. In Broughton, Simon and Ellingham, Mark with McConnachie, James and Duane, Orla (Ed.), ''World Music, Vol. 1: Africa, Europe and the Middle East'', pp 261–272. Rough Guides Ltd, Penguin Books. *Gilchrist, Jim. "Scotland". 2001. In Mathieson, Kenny (Ed.), ''Celtic music'', pp. 54–87. Backbeat Books.

a high-quality, free digital resource hosted b

BBC Radio Scotland

online radio: folk music on Travelling Folk, bagpipe music on Pipeline, country dance music on Reel Blend and Take the Floor. (RealPlayer plugin required)

Scottish Music Centre

music archive and information resource.

Gaelic Modes

Web articles on Gaelic harp harmony & modes {{Celtic music

Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

is internationally known for its traditional music, which remained vibrant throughout the 20th century and into the 21st, when many traditional forms worldwide lost popularity to pop music. In spite of emigration

Emigration is the act of leaving a resident country or place of residence with the intent to settle elsewhere (to permanently leave a country). Conversely, immigration describes the movement of people into one country from another (to permanentl ...

and a well-developed connection to music imported from the rest of Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, the music of Scotland has kept many of its traditional aspects; indeed, it has itself influenced many forms of music.

Many outsiders associate Scottish folk music almost entirely with the Great Highland Bagpipe

The Great Highland bagpipe ( gd, a' phìob mhòr "the great pipe") is a type of bagpipe native to Scotland, and the Scottish analogue to the Great Irish Warpipes. It has acquired widespread recognition through its usage in the British milit ...

, which has long played an important part in Scottish music. Although this particular form of bagpipe developed exclusively in Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

, it is not the only Scottish bagpipe. The earliest mention of bagpipes in Scotland dates to the 15th century although they are believed to have been introduced to Britain by the Roman armies. The ''pìob mhór'', or Great Highland Bagpipe, was originally associated with both hereditary piping families and professional pipers to various clan chiefs; later, pipes were adopted for use in other venues, including military marching. Piping clans included the Clan Henderson

The Clan Henderson (''Clann Eanruig'') is a Scottish clan.Way, George and Squire, Romily. (1994). ''Collins Scottish Clan & Family Encyclopedia''. (Foreword by The Rt Hon. The Earl of Elgin KT, Convenor, The Standing Council of Scottish Chiefs). ...

, MacArthurs, MacDonalds, MacKays

M&Co Trading Limited, previously Mackays Stores Limited until its 2020 administration, (previously trading as Mackays, now trading as M&Co.) is a Scottish chain store selling women's, men's, and children's clothes, as well as small homeware p ...

and, especially, the MacCrimmon, who were hereditary pipers to the Clan MacLeod

Clan MacLeod (; gd, Clann Mac Leòid ) is a Highland Scottish clan associated with the Isle of Skye. There are two main branches of the clan: the MacLeods of Harris and Dunvegan, whose chief is MacLeod of MacLeod, are known in Gaelic as ' ("see ...

.

Early music

Stringed instruments have been known in Scotland from at least the

Stringed instruments have been known in Scotland from at least the Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

. The first evidence of lyres were found in the Greco-Roman

The Greco-Roman civilization (; also Greco-Roman culture; spelled Graeco-Roman in the Commonwealth), as understood by modern scholars and writers, includes the geographical regions and countries that culturally—and so historically—were di ...

period on the Isle of Skye

The Isle of Skye, or simply Skye (; gd, An t-Eilean Sgitheanach or ; sco, Isle o Skye), is the largest and northernmost of the major islands in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. The island's peninsulas radiate from a mountainous hub dominated ...

(dating from 2300 BCE), making it Europe's oldest surviving stringed instrument. Bards

In Celtic cultures, a bard is a professional story teller, verse-maker, music composer, oral historian and genealogist, employed by a patron (such as a monarch or chieftain) to commemorate one or more of the patron's ancestors and to praise t ...

, who acted as musicians, but also as poets, story tellers, historians, genealogists and lawyers, relying on an oral tradition that stretched back generations, were found in Scotland as well as Wales and Ireland. Often accompanying themselves on the harp

The harp is a stringed musical instrument that has a number of individual strings running at an angle to its soundboard; the strings are plucked with the fingers. Harps can be made and played in various ways, standing or sitting, and in orche ...

, they can also be seen in records of the Scottish courts throughout the medieval period. Scottish church music from the later Middle Ages was increasingly influenced by continental developments, with figures like 13th-century musical theorist Simon Tailler studying in Paris, before returning to Scotland where he introduced several reforms of church music.K. Elliott and F. Rimmer, ''A History of Scottish Music'' (London: British Broadcasting Corporation, 1973), , pp. 8–12. Scottish collections of music like the 13th-century 'Wolfenbüttel 677', which is associated with St Andrews

St Andrews ( la, S. Andrea(s); sco, Saunt Aundraes; gd, Cill Rìmhinn) is a town on the east coast of Fife in Scotland, southeast of Dundee and northeast of Edinburgh. St Andrews had a recorded population of 16,800 , making it Fife's fou ...

, contain mostly French compositions, but with some distinctive local styles. The captivity of James I in England from 1406 to 1423, where he earned a reputation as a poet and composer, may have led him to take English and continental styles and musicians back to the Scottish court on his release. In the late 15th century a series of Scottish musicians trained in the Netherlands before returning home, including John Broune, Thomas Inglis and John Fety, the last of whom became master of the song school in Aberdeen and then Edinburgh, introducing the new five-fingered organ playing technique.J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , pp. 58 and 118. In 1501 James IV refounded the Chapel Royal within Stirling Castle

Stirling Castle, located in Stirling, is one of the largest and most important castles in Scotland, both historically and architecturally. The castle sits atop Castle Hill, an intrusive crag, which forms part of the Stirling Sill geological ...

, with a new and enlarged choir and it became the focus of Scottish liturgical music. Burgundian and English influences were probably reinforced when Henry VII's daughter Margaret Tudor married James IV in 1503.M. Gosman, A. A. MacDonald, A. J. Vanderjagt and A. Vanderjagt, ''Princes and Princely Culture, 1450–1650'' (Brill, 2003), , p. 163. James V (1512–42) was a major patron of music. A talented lute player, he introduced French chansons

A (, , french: chanson française, link=no, ; ) is generally any lyric-driven French song, though it most often refers to the secular polyphonic French songs of late medieval and Renaissance music. The genre had origins in the monophonic so ...

and consorts of viols to his court and was patron to composers such as David Peebles

David Peebles ables(d. 1579?) was a Scottish composer of religious music.

Biography

Little is known of his life but the majority of his work dates to between 1530 and 1576. He is known to have been a canon at the Augustinian Priory of St Andre ...

(c. 1510–1579?).

The Scottish Reformation

The Scottish Reformation was the process by which Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland broke with the Pope, Papacy and developed a predominantly Calvinist national Church of Scotland, Kirk (church), which was strongly Presbyterianism, Presbyterian in ...

, directly influenced by Calvinism

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Cal ...

, was generally opposed to church music, leading to the removal of organs and a growing emphasis on metrical psalms

A metrical psalter is a kind of Bible translation: a book containing a verse translation of all or part of the Book of Psalms in vernacular poetry, meant to be sung as hymns in a church. Some metrical psalters include melodies or harmonisatio ...

, including a setting by David Peebles commissioned by James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray

James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray (c. 1531 – 23 January 1570) was a member of the House of Stewart as the illegitimate son of King James V of Scotland, James V of Scotland. A supporter of his half-sister Mary, Queen of Scots, he was the regent ...

. The most important work in Scottish reformed music was probably ''A forme of Prayers'' published in Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

in 1564.R. M. Wilson, ''Anglican Chant and Chanting in England, Scotland, and America, 1660 to 1820'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), , pp. 146–7 and 196–7. The return from France of James V's daughter, Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legitimate child of James V of Scot ...

in 1561, renewed the Scottish court as a centre of musical patronage and performance. The Queen played the lute, virginals

The virginals (or virginal) is a keyboard instrument of the harpsichord family. It was popular in Europe during the late Renaissance and early Baroque periods.

Description

A virginal is a smaller and simpler rectangular or polygonal form of ...

and (unlike her father) was a fine singer.A. Frazer, ''Mary Queen of Scots'' (London: Book Club Associates, 1969), pp. 206–7. She brought many influences from the French court where she had been educated, employing lutenists and viol players in her household. Mary's position as a Catholic gave a new lease of life to the choir of the Scottish Chapel Royal in her reign, but the destruction of Scottish church organs meant that instrumentation to accompany the mass had to employ bands of musicians with trumpets, drums, fifes, bagpipes and tabors. The outstanding Scottish composer of the era was Robert Carver (c.1485–c.1570) whose works included the nineteen-part motet 'O Bone Jesu'. James VI, king of Scotland from 1567, was a major patron of the arts in general. He rebuilt the Chapel Royal at Stirling in 1594 and the choir was used for state occasions like the baptism of his son Henry.P. Le Huray, ''Music and the Reformation in England, 1549–1660'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978), , pp. 83–5. He followed the tradition of employing lutenists for his private entertainment, as did other members of his family.T. Carter and J. Butt, ''The Cambridge History of Seventeenth-Century Music'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), , pp. 280, 300, 433 and 541. When he came south to take the throne of England in 1603 as James I, he removed one of the major sources of patronage in Scotland. The Scottish Chapel Royal was now used only for occasional state visits, as when Charles I returned in 1633 to be crowned, bringing many musicians from the English Chapel Royal for the service, and it began to fall into disrepair. From now on the court in Westminster would be the only major source of royal musical patronage.

Folk music

There is evidence that there was a flourishing culture of popular music in Scotland during the late Middle Ages, but the only song with a melody to survive from this period is the "Pleugh Song".J. R. Baxter, "Music, ecclesiastical", in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 130–33. After theReformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

, the secular popular tradition of music continued, despite attempts by the kirk

Kirk is a Scottish and former Northern English word meaning "church". It is often used specifically of the Church of Scotland. Many place names and personal names are also derived from it.

Basic meaning and etymology

As a common noun, ''kirk'' ...

, particularly in the Lowlands, to suppress dancing and events like penny weddings.J. Porter, "Introduction" in J. Porter, ed., ''Defining Strains: The Musical Life of Scots in the Seventeenth Century'' (Peter Lang, 2007), , p. 22. This period saw the creation of the ceòl mór (the great music) of the bagpipe, which reflected its martial origins, with battle-tunes, marches, gatherings, salutes and laments. The Highlands in the early seventeenth century saw the development of piping families including the MacCrimmonds, MacArthurs, MacGregors and the Mackays of Gairloch

Gairloch ( ; gd, Geàrrloch , meaning "Short Loch") is a village, civil parish and community on the shores of Loch Gairloch in Wester Ross, in the North-West Highlands of Scotland. A tourist destination in the summer months, Gairloch has a go ...

. There is also evidence of adoption of the fiddle in the Highlands with Martin Martin

Martin Martin (Scottish Gaelic: Màrtainn MacGilleMhàrtainn) (-9 October 1718) was a Scottish writer best known for his work '' A Description of the Western Islands of Scotland'' (1703; second edition 1716). This book is particularly noted for ...

noting in his ''A Description of the Western Isles of Scotland'' (1703) that he knew of 18 players in Lewis alone.J. Porter, "Introduction" in J. Porter, ed., ''Defining Strains: The Musical Life of Scots in the Seventeenth Century'' (Peter Lang, 2007), , p. 35. Well-known musicians included the fiddler Pattie Birnie and the piper Habbie Simpson

Habbie Simpson (1550–1620) was the town piper in the Scottish village of Kilbarchan in Renfrewshire. Today Simpson is chiefly known as the subject of the poem the ''Lament for Habbie Simpson'' (also known as ''The life and death of the piper of ...

. This tradition continued into the nineteenth century, with major figures such as the fiddlers Neil

Neil is a masculine name of Gaelic and Irish origin. The name is an anglicisation of the Irish ''Niall'' which is of disputed derivation. The Irish name may be derived from words meaning "cloud", "passionate", "victory", "honour" or "champion".. A ...

and his son Nathaniel Gow

Nathaniel Gow (28 May 1763 – 19 January 1831) was a Scottish musician who was the fourth son of Niel Gow, and a celebrated performer, composer and arranger of tunes, songs and other pieces on his own right. He wrote about 200 compositions in ...

.J. R. Baxter, "Culture, Enlightenment (1660–1843): music", in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 140–1. There is evidence of ballad

A ballad is a form of verse, often a narrative set to music. Ballads derive from the medieval French ''chanson balladée'' or ''ballade'', which were originally "dance songs". Ballads were particularly characteristic of the popular poetry and ...

s from this period. Some may date back to the late Medieval era and deal with events and people that can be traced back as far as the thirteenth century. They remained an oral tradition until they were collected as folk songs in the eighteenth century."Popular Ballads" ''The Broadview Anthology of British Literature: The Restoration and the Eighteenth Century'' (Broadview Press, 2006), pp. 610–17.

The earliest printed collection of secular music comes from the seventeenth century. Collection began to gain momentum in the early eighteenth century and, as the kirk's opposition to music waned, there were a flood of publications including Allan Ramsay's verse compendium ''The Tea Table Miscellany'' (1723) and ''The Scots Musical Museum

The ''Scots Musical Museum'' was an influential collection of traditional folk music of Scotland published from 1787 to 1803. While it was not the first collection of Scottish folk songs and music, the six volumes with 100 songs in each collected ...

'' (1787 to 1803) by James Johnson and Robert Burns

Robert Burns (25 January 175921 July 1796), also known familiarly as Rabbie Burns, was a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland and is celebrated worldwide. He is the best known of the poets who hav ...

. From the late nineteenth century there was renewed interest in traditional music, which was more academic and political in intent.B. Sweers, ''Electric Folk: The Changing Face of English Traditional Music'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), , pp. 31–8. In Scotland collectors included the Reverend James Duncan and Gavin Greig

Gavin Greig (1856–1914) was a Scottish folksong collector, playwright, novelist and teacher.

He edited James Scott Skinner's biggest collection of music, ''The Harp and Claymore Collection'', providing harmonies for Skinner's compositions, and ...

. Major performers included James Scott Skinner

James Scott Skinner (5 August 1843 – 17 March 1927) was a Scottish dancing master, violinist, fiddler and composer. He is considered to be one of the most influential fiddlers in Scottish traditional music, and was known as "the Strathspey Kin ...

.J. R. Baxter, "Music, Highland", in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 434–5. This revival began to have a major impact on classical music, with the development of what was in effect a national school of orchestral and operatic music in Scotland, with composers that included Alexander Mackenzie, William Wallace

Sir William Wallace ( gd, Uilleam Uallas, ; Norman French: ; 23 August 1305) was a Scottish knight who became one of the main leaders during the First War of Scottish Independence.

Along with Andrew Moray, Wallace defeated an English army a ...

, Learmont Drysdale

Learmont Drysdale (full name George John Learmont Drysdale; 3 October 1866 – 18 June 1909) was a Scottish composer. During a short career he wrote music inspired by Scotland, particularly the Scottish Borders; this included orchestral music, c ...

, Hamish MacCunn

Hamish MacCunn, ''né'' James MacCunn (22 March 18682 August 1916) was a Scottish composer, conductor and teacher.

He was one of the first students of the newly-founded Royal College of Music in London, and quickly made a mark. As a composer he ...

and John McEwen

Sir John McEwen, (29 March 1900 – 20 November 1980) was an Australian politician who served as the 18th prime minister of Australia, holding office from 1967 to 1968 in a caretaker capacity after the disappearance of Harold Holt. He was the ...

.M. Gardiner, ''Modern Scottish Culture'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005), , pp. 195–6.

After World War II traditional music in Scotland was marginalised, but remained a living tradition. This marginal status was changed by individuals including Alan Lomax

Alan Lomax (; January 31, 1915 – July 19, 2002) was an American ethnomusicologist, best known for his numerous field recordings of folk music of the 20th century. He was also a musician himself, as well as a folklorist, archivist, writer, sch ...

, Hamish Henderson

Hamish Scott Henderson (11 November 1919 – 9 March 2002) was a Scottish poet, songwriter, communist, intellectual and soldier.

He was a catalyst for the folk revival in Scotland. He was also an accomplished folk song collector and dis ...

and Peter Kennedy, through collecting, publications, recordings and radio programmes.B. Sweers, ''Electric Folk: The Changing Face of English Traditional Music'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), , pp. 256–7. Acts that were popularised included John Strachan

John Strachan (; 12 April 1778 – 1 November 1867) was a notable figure in Upper Canada and the first Anglican Bishop of Toronto. He is best known as a political bishop who held many government positions and promoted education from common sc ...

, Jimmy MacBeath

Jimmy MacBeath (1894–1972) was a Scottish Traveller and Traditional singer of the Bothy Ballads from the north east of Scotland. He was both a mentor and source for fellow singers during the mid 20th century British folk revival. He had a hug ...

, Jeannie Robertson

Jeannie Robertson (1908 – 13 March 1975) was a Scottish folk singer.

Her most celebrated song is "I'm a Man You Don't Meet Every Day", otherwise known as "Jock Stewart", which was covered by Archie Fisher, The Dubliners, The McCalmans, ...

and Flora MacNeil

Flora MacNeil, MBE (6 October 1928 – 15 May 2015) was a Scottish Gaelic Traditional singer. MacNeil gained prominence after meeting Alan Lomax and Hamish Henderson during the early 1950s, and continued to perform into her later years.

Ea ...

. In the 1960s there was a flourishing folk club

A folk club is a regular event, permanent venue, or section of a venue devoted to folk music and traditional music. Folk clubs were primarily an urban phenomenon of 1960s and 1970s Great Britain and Ireland, and vital to the second British folk r ...

culture and Ewan MacColl

James Henry Miller (25 January 1915 – 22 October 1989), better known by his stage name Ewan MacColl, was a folk singer-songwriter, folk song collector, labour activist and actor. Born in England to Scottish parents, he is known as one of the ...

emerged as a leading figure in the revival in Britain.S. Broughton, M. Ellingham and R. Trillo, eds, ''World Music: Africa, Europe and the Middle East'' (London: Rough Guides, 1999), , pp. 261–3. They hosted traditional performers, including Donald Higgins and the Stewarts of Blairgowrie, beside English performers and new Scottish revivalists such as Robin Hall

Robin Hall (27 June 1936 – 18 November 1998) was a Scottish folksinger, best known as half of a singing duo with Jimmie Macgregor. Hall was a direct descendant of the famous Scottish folk hero and outlaw Rob Roy MacGregor as well as of th ...

, Jimmie Macgregor, The Corries

The Corries were a Scottish folk group that emerged from the Scottish folk revival of the early 1960s. The group was a trio from their formation until 1966 when founder Bill Smith left the band but Roy Williamson and Ronnie Browne continued ...

and the Ian Campbell Folk Group

The Ian Campbell Folk Group were one of the most popular and respected folk groups of the British folk revival of the 1960s. The group made many appearances on radio, television, and at national and international venues and festivals. They per ...

. There was also a strand of popular Scottish music that benefited from the arrival of radio and television, which relied on images of Scottishness derived from tartanry

Tartanry is the stereotypical or kitsch representation of traditional Scottish culture, particularly by the emergent Scottish tourist industry in the 18th and 19th centuries, and later by the American film industry. The earliest use of the word ...

and stereotypes employed in music hall

Music hall is a type of British theatrical entertainment that was popular from the early Victorian era, beginning around 1850. It faded away after 1918 as the halls rebranded their entertainment as variety. Perceptions of a distinction in Bri ...

and variety

Variety may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Entertainment formats

* Variety (radio)

* Variety show, in theater and television

Films

* ''Variety'' (1925 film), a German silent film directed by Ewald Andre Dupont

* ''Variety'' (1935 film), ...

. This was exemplified by the TV programme ''The White Heather Club

''The White Heather Club'' was a BBC TV Scottish variety show that ran on and off from 7 May 1958 to 11 April 1968

History

It was an early evening BBC television programme. It started at 6.20, and Jimmy Shand composed a melody "The Six Twenty ...

'' which ran from 1958 to 1967, hosted by Andy Stewart and starring Moira Anderson and Kenneth McKellar.

The fusing of various styles of American music with British folk created a distinctive form of fingerstyle guitar

Fingerstyle guitar is the technique of playing the guitar or bass guitar by plucking the strings directly with the fingertips, fingernails, or picks attached to fingers, as opposed to flatpicking (plucking individual notes with a single plectr ...

playing known as folk baroque

Folk baroque or baroque guitar, is a distinctive and influential guitar fingerstyle developed in Britain in the 1960s, which combined elements of American folk, blues, jazz and ragtime with British folk music to produce a new and elaborate form o ...

, pioneered by figures including Davey Graham

David Michael Gordon "Davey" Graham (originally spelled Davy Graham) (26 November 1940 – 15 December 2008) was a British guitarist and one of the most influential figures in the 1960s British folk revival. He inspired many famous practitioners ...

and Bert Jansch

Herbert Jansch (3 November 1943 – 5 October 2011) was a Scottish folk musician and founding member of the band Pentangle. He was born in Glasgow and came to prominence in London in the 1960s as an acoustic guitarist and singer-songwriter ...

. Others totally abandoned the traditional element including Donovan

Donovan Phillips Leitch (born 10 May 1946), known mononymously as Donovan, is a Scottish musician, songwriter, and record producer. He developed an eclectic and distinctive style that blended folk, jazz, pop, psychedelic rock and world mus ...

and The Incredible String Band

The Incredible String Band (sometimes abbreviated as ISB) were a Scottish psychedelic folk band formed by Clive Palmer (musician), Clive Palmer, Robin Williamson and Mike Heron in Edinburgh in 1966. The band built a considerable following, esp ...

, who have been seen as developing psychedelic folk

Psychedelic folk (sometimes acid folk or freak folk) is a loosely defined form of psychedelia that originated in the 1960s. It retains the largely acoustic instrumentation of folk, but adds musical elements common to psychedelic music.

Chara ...

. Acoustic groups who continued to interpret traditional material through into the 1970s included The Tannahill Weavers

The Tannahill Weavers are a band which performs traditional Scottish music. Releasing their first album in 1976, they became notable for being one of the first popular bands to incorporate the sound of the Great Highland Bagpipe in an ensemble ...

, Ossian, Silly Wizard

Silly Wizard was a Scottish folk band that began forming in Edinburgh in 1970. The founder members were two like-minded university students— Gordon Jones (guitar, bodhran, vocals, bouzouki, mandola), and Bob Thomas (guitar, mandolin, mand ...

, The Boys of the Lough

The Boys of the Lough is a Scottish-Irish Celtic music band active since the 1970s.

Early years

Their first album, called ''Boys of the Lough'' (1972) consisted of Aly Bain (fiddle), Cathal McConnell (flute), Dick Gaughan (vocals and guitar) and ...

, Battlefield Band

Battlefield Band were a Scottish traditional music group. Founded in Glasgow in 1969, they have released over 30 albums and undergone many changes of lineup. As of 2010, none of the original founders remain in the band.

The band is noted for t ...

, The Clutha

The Clutha were a traditional Scottish band hailing from Glasgow, that released a small number of albums in the 1970s. The line-up on the Clutha's first album, ''Scotia'' (1971), was John Eaglesham (vocal, concertina), Erlend Voy (fiddle, conc ...

and the Whistlebinkies.S. Broughton, M. Ellingham and R. Trillo, eds, ''World Music: Africa, Europe and the Middle East'' (London: Rough Guides, 1999), , pp. 267.

Celtic rock

Celtic rock is a genre of folk rock, as well as a form of Celtic fusion which incorporates Celtic music, instrumentation and themes into a rock music context. It has been extremely prolific since the early 1970s and can be seen as a key foundat ...

developed as a variant of British folk rock

British folk rock is a form of folk rock which developed in the United Kingdom from the mid 1960s, and was at its most significant in the 1970s. Though the merging of folk and rock music came from several sources, it is widely regarded that the ...

by Scottish groups including the JSD Band

The JSD Band was an influential Scottish-based Celtic and folk rock band primarily active from 1969 to 1974 and then again briefly from 1997 to 1998. The band released five full-length albums, and numerous singles and special releases, many of ...

and Spencer's Feat. Five Hand Reel

Five Hand Reel was a Scottish/English/Irish Celtic rock band of the late 1970s, that combined experiences of traditional Scottish and Irish folk music with electric rock arrangements. The members of the band were Dick Gaughan (born 17 May 1948) ...

, who combined Irish and Scottish personnel, emerged as the most successful exponents of the style. From the late 1970s the attendance at, and numbers of, folk clubs began to decrease, as new musical and social trends began to dominate. However, in Scotland the circuit of ceilidhs and festivals helped prop up traditional music. Two of the most successful groups of the 1980s that emerged from this dance band circuit were Runrig

Runrig were a Scottish Celtic rock band formed on the Isle of Skye in 1973. From its inception, the band's line-up included songwriters Rory Macdonald and Calum Macdonald. The line-up during most of the 1980s and 1990s (the band's most succe ...

and Capercaillie. A by-product of the Celtic Diaspora was the existence of large communities across the world that looked for their cultural roots and identity to their origins in the Celtic nations. From the US this includes Scottish bands Seven Nations, Prydein and Flatfoot 56

Flatfoot 56 is an American Celtic punk band from Chicago, Illinois, that formed in 2000. The group's use of Scottish Highland bagpipes has led to their classification as a Celtic punk band.

History

The band formed in summer 2000 as a three-piece ...

. From Canada are bands such as Enter the Haggis

Enter the Haggis is a Canadian Celtic rock band based in Toronto. The band was founded in 1995 by Craig Downie, the only remaining original member in the lineup, which currently consists of Downie ( highland bagpipes, vocals), Brian Buchanan (vo ...

, Great Big Sea

Great Big Sea was a Canadian folk rock band from Newfoundland and Labrador, best known for performing energetic rock interpretations of traditional Newfoundland folk songs including sea shanties, which draw from the island's 500-year Irish, Scot ...

, The Real McKenzies

The Real McKenzies is a Canadian Celtic punk band founded in 1992 and based in Vancouver, British Columbia. They are one of the founders of the Celtic punk movement, albeit 10 years after The Pogues.

In addition to writing and performing origin ...

and Spirit of the West

Spirit of the West were a Canadian folk rock band from North Vancouver, active from 1983 to 2016. They were popular on the Canadian folk music scene in the 1980s before evolving a blend of hard rock, Britpop, and Celtic folk influences which ma ...

.

Classical music

The development of a distinct tradition ofart music

Art music (alternatively called classical music, cultivated music, serious music, and canonic music) is music considered to be of high phonoaesthetic value. It typically implies advanced structural and theoretical considerationsJacques Siron, ...

in Scotland was limited by the impact of the Scottish Reformation

The Scottish Reformation was the process by which Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland broke with the Pope, Papacy and developed a predominantly Calvinist national Church of Scotland, Kirk (church), which was strongly Presbyterianism, Presbyterian in ...

on ecclesiastical music from the sixteenth century. Concerts, largely composed of "Scottish airs", developed in the seventeenth century and classical instruments were introduced to the country. Music in Edinburgh prospered through the patronage of figures including the merchant Sir John Clerk of Penicuik

John Clerk of Penicuik (1611–1674) was a Scottish merchant noted for maintaining a comprehensive archive of family papers, now held by the National Archives of Scotland and the National Library of Scotland.

Background

Born in Montrose, he wa ...

. The Italian style of classical music was probably first brought to Scotland by the cellist and composer Lorenzo Bocchi, who travelled to Scotland in the 1720s. The Musical Society of Edinburgh was incorporated in 1728. Several Italian musicians were active in the capital in this period and there are several known Scottish composers in the classical style, including Thomas Erskine, 6th Earl of Kellie

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the A ...

, the first Scot known to have produced a symphony

A symphony is an extended musical composition in Western classical music, most often for orchestra. Although the term has had many meanings from its origins in the ancient Greek era, by the late 18th century the word had taken on the meaning com ...

.N. Wilson, ''Edinburgh'' (Lonely Planet, 3rd edn., 2004), , p. 33.

In the mid-eighteenth century a group of Scottish composers including James Oswald and William McGibbon created the "Scots drawing room style", taking primarily Lowland Scottish tunes and making them acceptable to a middle class audience. In the 1790s Robert Burns

Robert Burns (25 January 175921 July 1796), also known familiarly as Rabbie Burns, was a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland and is celebrated worldwide. He is the best known of the poets who hav ...

embarked on an attempt to produce a corpus of Scottish national song contributing about a third of the songs of ''The Scots Musical Museum

The ''Scots Musical Museum'' was an influential collection of traditional folk music of Scotland published from 1787 to 1803. While it was not the first collection of Scottish folk songs and music, the six volumes with 100 songs in each collected ...

''. Burns also collaborated with George Thomson in ''A Select Collection of Original Scottish Airs'', which adapted Scottish folk songs with "classical" arrangements. However, Burns' championing of Scottish music may have prevented the establishment of a tradition of European concert music in Scotland, which faltered towards the end of the eighteenth century.

From the mid-nineteenth century classical music began a revival in Scotland, aided by the visits of Chopin and Mendelssohn

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (3 February 18094 November 1847), born and widely known as Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic music, Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositi ...

in the 1840s.A. C. Cheyne, "Culture: age of industry, (1843–1914), general", in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 143–6. By the late nineteenth century, there was in effect a national school of orchestral and operatic music in Scotland, with major composers including Alexander Mackenzie, William Wallace

Sir William Wallace ( gd, Uilleam Uallas, ; Norman French: ; 23 August 1305) was a Scottish knight who became one of the main leaders during the First War of Scottish Independence.

Along with Andrew Moray, Wallace defeated an English army a ...

, Learmont Drysdale

Learmont Drysdale (full name George John Learmont Drysdale; 3 October 1866 – 18 June 1909) was a Scottish composer. During a short career he wrote music inspired by Scotland, particularly the Scottish Borders; this included orchestral music, c ...

and Hamish MacCunn

Hamish MacCunn, ''né'' James MacCunn (22 March 18682 August 1916) was a Scottish composer, conductor and teacher.

He was one of the first students of the newly-founded Royal College of Music in London, and quickly made a mark. As a composer he ...

. Major performers included the pianist Frederic Lamond, and singers Mary Garden

A Mary garden is a small sacred garden enclosing a statue or shrine of the Virgin Mary, who is known to many Christians as the Blessed Virgin, Our Lady, or the Mother of God. In the New Testament, Mary is the mother of Jesus of Nazareth. Mary ...

and Joseph Hislop

Joseph Hislop (5 April 18846 May 1977) was a Scottish lyric tenor who appeared in opera and oratorio and gave concerts around the world. He sang at La Scala, Milan, the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London, and the Opéra-Comique, Paris, a ...

.C. Harvie, ''No Gods and Precious Few Heroes: Twentieth-century Scotland'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998), , pp. 136–8.

After World War I, Robin Orr

Robert Kemsley (Robin) Orr (2 June 1909 – 9 April 2006) was a Scottish organist and composer.

Life

Born in Brechin, and educated at Loretto School, he studied the organ at the Royal College of Music in London under Walter Galpin Alcock, and pi ...

and Cedric Thorpe Davie were influenced by modernism

Modernism is both a philosophy, philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western world, Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new fo ...

and Scottish musical cadences. Erik Chisholm

Erik William Chisholm (4 January 1904 – 8 June 1965) was a Scottish composer, pianist, organist and conductor sometimes known as "Scotland's forgotten composer". According to his biographer, Chisholm "was the first composer to absorb Celtic i ...

founded the Scottish Ballet Society and helped create several ballets.M. Gardiner, ''Modern Scottish Culture'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005), , pp. 193–8. The Edinburgh Festival

__NOTOC__

This is a list of arts and cultural festivals regularly taking place in Edinburgh, Scotland.

The city has become known for its festivals since the establishment in 1947 of the Edinburgh International Festival and the Edinburgh Fe ...

was founded in 1947 and led to an expansion of classical music in Scotland, leading to the foundation of Scottish Opera

Scottish Opera is the national opera company of Scotland, and one of the five national performing arts companies of Scotland. Founded in 1962 and based in Glasgow, it is the largest performing arts organisation in Scotland.

History

Scottish Op ...

in 1960. Important post-war composers included Ronald Stevenson

Ronald James Stevenson (6 March 1928 – 28 March 2015) was a Scottish composer, pianist, and writer about music.

Biography

The son of a Scottish father and Welsh mother, Stevenson was born in Blackburn, Lancashire, in 1928. He studied at the ...

, Francis George Scott

Francis George Scott (25 January 1880 – 6 November 1958) was a Scottish composer often associated with the Scottish Renaissance.

Born at 6 Oliver Crescent, Hawick, Roxburghshire, he was the son of a supplier of mill-engineering parts. Educate ...

, Edward McGuire, William Sweeney, Iain Hamilton, Thomas Wilson, Thea Musgrave

Thea Musgrave CBE (born 27 May 1928) is a Scottish composer of opera and classical music. She has lived in the United States since 1972.

Biography

Born in Barnton, Edinburgh, Musgrave was educated at Moreton Hall School, a boarding independent ...

, Judith Weir

Judith Weir (born 11 May 1954) is a British composer serving as Master of the King's Music. Appointed in 2014 by Queen Elizabeth II, Weir is the first woman to hold this office.

Biography

Weir was born in Cambridge, England, to Scottish paren ...

, James MacMillan

Sir James Loy MacMillan, (born 16 July 1959) is a Scottish classical composer and conductor.

Early life

MacMillan was born at Kilwinning, in North Ayrshire, but lived in the East Ayrshire town of Cumnock until 1977. His father is James MacMi ...

and Helen Grime

Helen Grime (born 1981) is a Scottish composer whose work, ''Virga'', was selected as one of the best ten new classical works of the 2000s by the Royal Scottish National Orchestra.

Though she was born in York, England, Grime's parents returned ...

. Craig Armstrong has produced music for numerous films. Major performers include the percussionist Evelyn Glennie

Dame Evelyn Elizabeth Ann Glennie, (born 19 July 1965) is a Scottish people, Scottish percussionist. She was selected as one of the two laureates for the Polar Music Prize of 2015.

Early life

Glennie was born in Methlick, Aberdeenshire in Sco ...

. Major Scottish orchestras include: Royal Scottish National Orchestra

The Royal Scottish National Orchestra (RSNO) ( gd, Orcastra Nàiseanta Rìoghail na h-Alba) is a British orchestra, based in Glasgow, Scotland. It is one of the five National performing arts companies of Scotland, national performing arts compa ...

(RSNO), the Scottish Chamber Orchestra

The Scottish Chamber Orchestra (SCO) is an Edinburgh-based UK chamber orchestra. One of Scotland's five National Performing Arts Companies, the SCO performs throughout Scotland, including annual tours of the Scottish Highlands and Islands and S ...

(SCO) and the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra

The BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra (BBC SSO) is a Scottish broadcasting symphony orchestra based in Glasgow. One of five full-time orchestras maintained by the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), it is the oldest full-time professional rad ...

(BBC SSO). Major venues include Glasgow Royal Concert Hall

Glasgow Royal Concert Hall is a concert and arts venue located in Glasgow, Scotland. It is owned by Glasgow City Council and operated by Glasgow Life, an agency of Glasgow City Council, which also runs Glasgow's City Halls and Old Fruitmarket v ...

, Usher Hall

The Usher Hall is a concert hall in Edinburgh, Scotland. It has hosted concerts and events since its construction in 1914 and can hold approximately 2,200 people in its recently restored auditorium, which is well loved by performers due to its ...

, Edinburgh and Queen's Hall, Edinburgh

The Queen's Hall is a performance venue in the Southside, Edinburgh, Scotland. The building opened in 1824 as Hope Park Chapel and reopened as the Queen's Hall in 1979.

Hope Park Chapel opened as a chapel of ease within the West Kirk parish i ...

.J. Clough, K. Davidson, S. Randall, A. Scott, ''DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Scotland: Scotland'' (London: Dorling Kindersley, 2012), , p. 108.N. Wilson, ''Edinburgh'' (London: Lonely Planet, 2004), , p. 137.

Pop, rock and fusion

Pop and rock were slow to get started in Scotland and produced few bands of note in the 1950s or 1960s, though thanks to accolades by

Pop and rock were slow to get started in Scotland and produced few bands of note in the 1950s or 1960s, though thanks to accolades by David Bowie

David Robert Jones (8 January 194710 January 2016), known professionally as David Bowie ( ), was an English singer-songwriter and actor. A leading figure in the music industry, he is regarded as one of the most influential musicians of the ...

and others, the Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

-based band 1-2-3 (later Clouds

In meteorology, a cloud is an aerosol consisting of a visible mass of miniature liquid droplets, frozen crystals, or other particles suspended in the atmosphere of a planetary body or similar space. Water or various other chemicals may com ...

), active 1966–71, have belatedly been acknowledged as a definitive precursor of the progressive rock movement. However, by the 1970s bands such as the Average White Band

The Average White Band (also known as AWB) are a Scottish funk and R&B band that had a series of soul and disco hits between 1974 and 1980. They are best known for their million-selling instrumental track " Pick Up the Pieces", and their album ...

, Nazareth

Nazareth ( ; ar, النَّاصِرَة, ''an-Nāṣira''; he, נָצְרַת, ''Nāṣəraṯ''; arc, ܢܨܪܬ, ''Naṣrath'') is the largest city in the Northern District of Israel. Nazareth is known as "the Arab capital of Israel". In ...

, and The Sensational Alex Harvey Band

The Sensational Alex Harvey Band were a Scottish rock band formed in Glasgow in 1972. Fronted by Alex Harvey accompanied by Zal Cleminson on guitar, bassist Chris Glen, keyboard player Hugh McKenna (1949–2019) and drummer Ted McKenna, thei ...

began to have international success. However, the biggest Scottish pop act of the 1970s (at least in terms of sales) were undoubtedly the Bay City Rollers

The Bay City Rollers are a Scottish pop rock band known for their worldwide teen idol popularity in the 1970s. They have been called the "tartan teen sensations from Edinburgh" and one of many acts heralded as the "biggest group since the Beat ...

; a spinoff band formed by former Rollers members, Pilot

An aircraft pilot or aviator is a person who controls the flight of an aircraft by operating its directional flight controls. Some other aircrew members, such as navigators or flight engineers, are also considered aviators, because they a ...

, also enjoyed some success. Several members of the internationally successful rock band AC/DC

AC/DC (stylised as ACϟDC) are an Australian Rock music, rock band formed in Sydney in 1973 by Scottish-born brothers Malcolm Young, Malcolm and Angus Young. Their music has been variously described as hard rock, blues rock, and Heavy metal ...

were born in Scotland, including original lead singer Bon Scott

Ronald Belford "Bon" Scott (9 July 1946 – 19 February 1980) was an Australian singer and songwriter. He was the lead vocalist and lyricist of the hard rock band AC/DC from 1974 until his death in 1980.

Born in Forfar in Angus, Scotlan ...

and guitarists Malcolm

Malcolm, Malcom, Máel Coluim, or Maol Choluim may refer to:

People

* Malcolm (given name), includes a list of people and fictional characters

* Clan Malcolm

* Maol Choluim de Innerpeffray, 14th-century bishop-elect of Dunkeld

Nobility

* Máe ...

and Angus Young

Angus McKinnon Young (born 31 March 1955) is an Australian musician, best known as the co-founder, lead guitarist, songwriter, and only remaining original member of the hard rock band AC/DC. He is known for his energetic performances, schoolbo ...

, though by the time they began playing, all three had moved to Australia. George Young, Angus and Malcolm's older brother, found success as a member of the Australian band The Easybeats

The Easybeats were an Australian rock band that formed in Sydney in late 1964. They enjoyed a level of success that in Australia rivalled The Beatles. They became the first Australian rock act to score an international hit, with the 1966 sing ...

, later produced some of AC/DC's records and formed a songwriting partnership with Dutch expat Harry Vanda

Johannes Hendrikus Jacob van den Berg (born 22 March 1946), better known as his stage name Harry Vanda, is a Dutch Australian musician, songwriter and record producer. He is best known as lead guitarist of the 1960s Australian rock band the Easy ...

. Similarly Mark Knopfler

Mark Freuder Knopfler (born 12 August 1949) is a British singer-songwriter, guitarist, and record producer. Born in Scotland and raised in England, he was the lead guitarist, singer and songwriter of the rock band Dire Straits. He pursued a s ...

and John Martyn

Iain David McGeachy (11 September 1948 – 29 January 2009), known professionally as John Martyn, was a Scottish singer-songwriter and guitarist. Over a 40-year career, he released 23 studio albums, and received frequent critical acclaim. ...

were partly raised in Scotland.

During the 1960s, Scotland contributed two innovative rock musicians who were central to the international scene; folk/psychedelia guitarist/singer/songwriter Donovan

Donovan Phillips Leitch (born 10 May 1946), known mononymously as Donovan, is a Scottish musician, songwriter, and record producer. He developed an eclectic and distinctive style that blended folk, jazz, pop, psychedelic rock and world mus ...

(Donovan Phillips Leitch), and blues-rock/jazz-rock bassist/composer Jack Bruce

John Symon Asher Bruce (14 May 1943 – 25 October 2014) was a Scottish bassist, singer-songwriter, musician and composer. He gained popularity as the primary lead vocalist and bassist of British rock band Cream. After the group disbande ...

(John Symon Asher Bruce). Traces of Scottish literary and musical influences can be found in both Donovan's and Bruce's work.''The Autobiography of Donovan; The Hurdy Gurdy Man''''Jack Bruce; Composing Himself'' by Harry Shapiro

Donovan

Donovan Phillips Leitch (born 10 May 1946), known mononymously as Donovan, is a Scottish musician, songwriter, and record producer. He developed an eclectic and distinctive style that blended folk, jazz, pop, psychedelic rock and world mus ...

's music on 1965's ''Fairytale'' anticipated the British folk rock

British folk rock is a form of folk rock which developed in the United Kingdom from the mid 1960s, and was at its most significant in the 1970s. Though the merging of folk and rock music came from several sources, it is widely regarded that the ...

revival. Donovan pioneered psychedelic rock

Psychedelic rock is a rock music Music genre, genre that is inspired, influenced, or representative of psychedelia, psychedelic culture, which is centered on perception-altering hallucinogenic drugs. The music incorporated new electronic sound ...

with Sunshine Superman in 1966. Donovan

Donovan Phillips Leitch (born 10 May 1946), known mononymously as Donovan, is a Scottish musician, songwriter, and record producer. He developed an eclectic and distinctive style that blended folk, jazz, pop, psychedelic rock and world mus ...

's decidedly Celtic rock

Celtic rock is a genre of folk rock, as well as a form of Celtic fusion which incorporates Celtic music, instrumentation and themes into a rock music context. It has been extremely prolific since the early 1970s and can be seen as a key foundat ...

directions can be found on his later albums like '' Open Road'' and '' HMS Donovan''. Donovan is said to be an early influence and encouragement for Marc Bolan

Marc Bolan ( ; born Mark Feld; 30 September 1947 – 16 September 1977) was an English guitarist, singer and songwriter. He was a pioneer of the glam rock movement in the early 1970s with his band T. Rex. Bolan was posthumously inducted int ...

founder of T. Rex.

Jack Bruce

John Symon Asher Bruce (14 May 1943 – 25 October 2014) was a Scottish bassist, singer-songwriter, musician and composer. He gained popularity as the primary lead vocalist and bassist of British rock band Cream. After the group disbande ...

co-founded Cream

Cream is a dairy product composed of the higher-fat layer skimmed from the top of milk before homogenization. In un-homogenized milk, the fat, which is less dense, eventually rises to the top. In the industrial production of cream, this process ...

along with Eric Clapton

Eric Patrick Clapton (born 1945) is an English rock and blues guitarist, singer, and songwriter. He is often regarded as one of the most successful and influential guitarists in rock music. Clapton ranked second in ''Rolling Stone''s list of ...

and Ginger Baker

Peter Edward "Ginger" Baker (19 August 1939 – 6 October 2019) was an English drummer. His work in the 1960s and 1970s earned him the reputation of "rock's first superstar drummer", for a style that melded jazz and Music of Africa, Africa ...

in 1966, debuting with the album ''Fresh Cream

''Fresh Cream'' is the debut studio album by the British rock band Cream. The album was released in the UK on 9 December 1966, as the first LP on the Reaction Records label, owned by producer Robert Stigwood. The UK album was released in both ...

''. ''Fresh Cream'' and the launch of Cream are considered a pivotal moment in blues-rock history, introducing virtuosity and improvisation to the form. Bruce, as a member of The Tony Williams Lifetime

The Tony Williams Lifetime was a jazz fusion group led by jazz drummer Tony Williams.

Original line-up

The Tony Williams Lifetime was founded in 1969 as a power trio with John McLaughlin on electric guitar, and Larry Young on organ. The band ...

(along with John McLaughlin John or Jon McLaughlin may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* John McLaughlin (musician) (born 1942), English jazz fusion guitarist, member of Mahavishnu Orchestra

* Jon McLaughlin (musician) (born 1982), American singer-songwriter

* John McLaug ...

and Larry Young) on ''Emergency!

''Emergency!'' is an American action-adventure medical drama television series jointly produced by Mark VII Limited and Universal Television. Debuting on NBC as a midseason replacement on January 15, 1972, replacing the two short-lived situatio ...

'', similarly contributed to a seminal jazz-rock work that predated Bitches Brew

''Bitches Brew'' is a studio album by American jazz trumpeter, composer, and bandleader Miles Davis. It was recorded from August 19 to 21, 1969, at Columbia's Studio B in New York City and released on March 30, 1970 by Columbia Records. It marke ...

by Miles Davis

Miles Dewey Davis III (May 26, 1926September 28, 1991) was an American trumpeter, bandleader, and composer. He is among the most influential and acclaimed figures in the history of jazz and 20th-century music. Davis adopted a variety of music ...

.

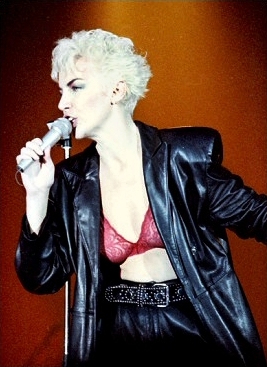

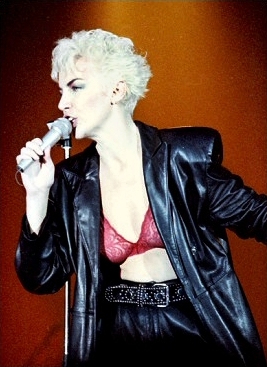

Scotland produced a few punk bands of note, such as

Scotland produced a few punk bands of note, such as The Exploited

The Exploited are a Scottish punk rock band from Edinburgh, formed in 1979 by Stevie Ross and Terry Buchan, with Buchan soon replaced by his brother Wattie Buchan. They signed to Secret Records in March 1981,The Rezillos

The Rezillos are a punk/ new wave band formed in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1976. Although emerging at the same time as other bands in the punk rock movement, the Rezillos did not share the nihilism or social commentary of their contemporaries, b ...

, The Skids

Skids are a Scottish punk rock and new wave band, formed in Dunfermline in 1977 by Stuart Adamson (guitar, keyboards, percussion and backing vocals), William Simpson (bass guitar and backing vocals), Thomas Kellichan (drums) and Richard Jo ...

, The Fire Engines

The Fire Engines were a post-punk band from Edinburgh, Scotland.

The Fire Engines were an influence on many bands that followed, including Franz Ferdinand and The Rapture, with Meat Whiplash and The Candyskins both taking their names from Fire ...

, and the Scars

A scar (or scar tissue) is an area of fibrous tissue that replaces normal skin after an injury. Scars result from the biological process of wound repair in the skin, as well as in other organs, and tissues of the body. Thus, scarring is a natu ...

. However, it was not until the post-punk

Post-punk (originally called new musick) is a broad genre of punk music that emerged in the late 1970s as musicians departed from punk's traditional elements and raw simplicity, instead adopting a variety of avant-garde sensibilities and non-roc ...

era of the early 1980s, that Scotland really came into its own, with bands like Cocteau Twins

Cocteau Twins was a Scottish rock band active from 1979 to 1997. They were formed in Grangemouth by Robin Guthrie (guitars, drum machine) and Will Heggie (bass), adding Elizabeth Fraser (vocals) in 1981 and replacing Heggie with multi-instrum ...

, Orange Juice

Orange juice is a liquid extract of the orange (fruit), orange tree fruit, produced by squeezing or reaming oranges. It comes in several different varieties, including blood orange, navel oranges, valencia orange, clementine, and tangerine. A ...

, The Associates, Simple Minds

Simple Minds are a Scottish rock band formed in Glasgow in 1977. They have released a string of hit singles, becoming best known internationally for "Don't You (Forget About Me)" (1985), which topped the '' Billboard'' Hot 100 in the United St ...

, Maggie Reilly

Maggie Reilly (born 15 September 1956) is a Scottish singer best known for her collaborations with the composer and instrumentalist Mike Oldfield. Most notably, she performed lead vocals on the Oldfield songs " Family Man", "Moonlight Shadow", ...

, Annie Lennox

Ann Lennox (born 25 December 1954) is a Scottish singer-songwriter, political activist and philanthropist. After achieving moderate success in the late 1970s as part of the New wave music, new wave band the Tourists, she and fellow musician D ...

(Eurythmics

Eurythmics were a British pop duo consisting of Annie Lennox and Dave Stewart. They were both previously in The Tourists, a band which broke up in 1980. The duo released their first studio album, '' In the Garden'', in 1981 to little succ ...

), Hue and Cry

In common law, a hue and cry is a process by which bystanders are summoned to assist in the apprehension of a criminal who has been witnessed in the act of committing a crime.

History

By the Statute of Winchester of 1285, 13 Edw. I statute 2. c ...

, Goodbye Mr Mackenzie

Goodbye Mr Mackenzie is a Scottish rock band formed in Bathgate near Edinburgh. At the band's commercial peak, the line-up consisted of Martin Metcalfe on vocals, John Duncan on guitar, Fin Wilson on bass guitar, Shirley Manson and Rona Scobi ...

, The Jesus and Mary Chain

The Jesus and Mary Chain are a Scottish alternative rock band formed in East Kilbride in 1983. The band revolves around the songwriting partnership of brothers Jim and William Reid. After signing to independent label Creation Records, they rele ...

, Wet Wet Wet

Wet Wet Wet are a Scottish soft rock band formed in 1982. They scored a number of hits in the UK charts and around the world in the 1980s and 1990s. They are best known for their 1994 cover of The Troggs' 1960s hit " Love Is All Around", which ...

, Big Country

Big Country are a Scottish rock band formed in Dunfermline, Fife, in 1981.

The height of the band's popularity was in the early to mid 1980s, although it has retained a cult following for many years since. The band's music incorporated Scott ...

, The Proclaimers

''The'' () is a grammatical Article (grammar), article in English language, English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite ...

and Josef K. Since the 1980s Scotland has produced several popular rock and alternative rock

Alternative rock, or alt-rock, is a category of rock music that emerged from the independent music underground of the 1970s and became widely popular in the 1990s. "Alternative" refers to the genre's distinction from Popular culture, mainstre ...

acts.

Most recently, Scottish piping has included a renaissance for cauldwind pipes such as smallpipes and border pipes, which use cold, dry air as opposed to the moist air of mouth-blown pipes. Other pipers such as Gordon Duncan and Fred Morrison

Fred Morrison (born 1963 in Bishopton, Renfrewshire) is a Scottish musician and composer. He has performed professionally on the Great Highland Bagpipes, Scottish smallpipes, Border pipes, low whistle, Northumbrian Smallpipes and uilleann pipe ...

began to explore new musical genres on many kinds of pipes. The accordion

Accordions (from 19th-century German ''Akkordeon'', from ''Akkord''—"musical chord, concord of sounds") are a family of box-shaped musical instruments of the bellows-driven free-reed aerophone type (producing sound as air flows past a reed ...

also gained in popularity during the 1970s due to the renown of Phil Cunningham, whose distinctive piano accordion style was an integral part of the band Silly Wizard

Silly Wizard was a Scottish folk band that began forming in Edinburgh in 1970. The founder members were two like-minded university students— Gordon Jones (guitar, bodhran, vocals, bouzouki, mandola), and Bob Thomas (guitar, mandolin, mand ...

. Numerous musicians continued to follow more traditional styles including Alex Beaton.

A more recent trend has been to fuse traditional Celtic with world music, rock and jazz (see Celtic fusion). This has been championed by musicians such as Shooglenifty

Shooglenifty are a Scottish, Edinburgh-based six-piece Celtic fusion band that tours internationally. The band blends Scottish traditional music with influences ranging from electronica to alternative rock. They contributed to Afro Celt Sound S ...

, innovators of the house

A house is a single-unit residential building. It may range in complexity from a rudimentary hut to a complex structure of wood, masonry, concrete or other material, outfitted with plumbing, electrical, and heating, ventilation, and air condi ...

fusion acid croft, Peatbog Faeries

The Peatbog Faeries are a largely instrumental Celtic fusion band. Formed in 1991, they are based in Dunvegan on the Isle of Skye, Scotland.

Their music embodies many styles and influences, including folk, electronica, African pop, rock and ...

, The Easy Club

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the m ...

, jazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with its roots in blues and ragtime. Since the 1920s Jazz Age, it has been recognized as a major ...

fusion bands, puirt à beul Puirt à beul (, literally "tunes from a mouth") is a traditional form of song native to Scotland (known as ''portaireacht'' in Ireland) that sets Gaelic lyrics to instrumental tune melodies. Historically, they were used to accompany dancing in the ...

mouth musicians Talitha MacKenzie and Martin Swan

Martin Swan (born Sheffield, England) is a Scottish multi-instrumentalist, songwriter, composer, record producer, recording engineer and instrument designer.

Swan is best known as the leader of the Mouth Music project, whose combination of tra ...

, pioneering singers Savourna Stevenson

Savourna Stevenson (born 1961) is a Scottish clàrsach player and composer.

Her father is the Scottish composer Ronald Stevenson. Actress Gerda Stevenson is her sister.

Her musical career began in the late 1970s; at the age of 15, she was alr ...

and Christine Primrose. Other modern musicians include the late techno-piper Martyn Bennett

Martyn Bennett (17 February 1971 – 30 January 2005) was a Canadian-Scottish musician who was influential in the evolution of modern Celtic fusion, a blending of traditional Celtic and modern music. He was a piper, violinist, composer and prod ...

(who used hip hop beats and sampling), Hamish Moore

Hamish Moore is a Scottish musician and bagpipe maker. Among Moore's contributions to Scottish music are his development of a revived form of the bellows-blown Scottish smallpipes; his 1985 recording of the Lowland and smallpipes, ''Cauld Wind Pi ...

, Roger Ball, Hamish Stuart

James Hamish Stuart (born 8 October 1949) is a British guitarist, bassist, singer, composer and record producer. He was an original member of the Average White Band.

Biography

Born in Glasgow, Scotland, Stuart attended Queens Park School in ...

, Jim Diamond and Sheena Easton

Sheena Shirley Easton (; born 27 April 1959) is a Scottish singer and actress. Easton came into the public eye in an episode of the first British musical reality television programme '' The Big Time: Pop Singer'', which recorded her attempts to ...

.

Scotland produced many indie bands in the 1980s, including Primal Scream

Primal Scream are a Scottish rock band originally formed in 1982 in Glasgow by Bobby Gillespie (vocals) and Jim Beattie. The band's current lineup consists of Gillespie, Andrew Innes (guitar), Simone Butler (bass), and Darrin Mooney (drums) ...

, The Soup Dragons

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the ...

, The Jesus and Mary Chain

The Jesus and Mary Chain are a Scottish alternative rock band formed in East Kilbride in 1983. The band revolves around the songwriting partnership of brothers Jim and William Reid. After signing to independent label Creation Records, they rele ...

, The Blue Nile

The Blue Nile was a Scottish band which originated in Glasgow. The group's early music was built heavily on synthesizers and electronic instrumentation and percussion, although later works featured guitar more prominently. Following early champ ...

, Teenage Fanclub

Teenage Fanclub are a Scottish alternative rock band formed in Bellshill near Glasgow in 1989. The group were founded by Norman Blake (vocals, guitar), Raymond McGinley (vocals, lead guitar) and Gerard Love (vocals, bass), all of whom shared ...

, 18 Wheeler, The Pastels

The Pastels are an indie rock group from Glasgow formed in 1981. They were a key act of the Scottish and British independent music scenes of the 1980s, and are specifically credited for the development of an independent and confident music scen ...

and BMX Bandits being some of the best examples. The following decade also saw a burgeoning scene in Glasgow, with the likes of The Almighty, Arab Strap

Arab Strap are a Scottish indie rock band whose core members are Aidan Moffat and Malcolm Middleton. The band were signed to independent record label Chemikal Underground, split in 2006 and reformed in 2016. The band signed to Rock Action Rec ...

, Belle and Sebastian

Belle and Sebastian are a Scottish indie pop band formed in Glasgow in 1996. Led by Stuart Murdoch, the band has released eleven albums. They are often compared with acts such as The Smiths and Nick Drake. The name "Belle and Sebastian" come ...

, Camera Obscura

A camera obscura (; ) is a darkened room with a aperture, small hole or lens at one side through which an image is 3D projection, projected onto a wall or table opposite the hole.

''Camera obscura'' can also refer to analogous constructions su ...

, The Delgados

The Delgados are a Scottish indie rock band formed in Glasgow in 1994. The band is composed of Alun Woodward (vocals, guitar), Emma Pollock (vocals, guitar), Stewart Henderson (bass guitar), and Paul Savage (drums).

Biography

The band was fo ...

, Bis and Mogwai

Mogwai () are a Scottish post-rock band, formed in 1995 in Glasgow. The band consists of Stuart Braithwaite (guitar, vocals), Barry Burns (guitar, piano, synthesizer, vocals), Dominic Aitchison (bass guitar), and Martin Bulloch (drums). Mogw ...

.

The late 1990s and 2000s saw Scottish guitar bands continue to achieve critical or commercial success, examples include

The late 1990s and 2000s saw Scottish guitar bands continue to achieve critical or commercial success, examples include Franz Ferdinand

Archduke Franz Ferdinand Carl Ludwig Joseph Maria of Austria, (18 December 1863 – 28 June 1914) was the heir presumptive to the throne of Austria-Hungary. His assassination in Sarajevo was the most immediate cause of World War I.

Fr ...

, Frightened Rabbit

Frightened Rabbit were a Scottish indie rock band from Selkirk, formed in 2003. Initially a solo project for vocalist and guitarist Scott Hutchison, the final lineup of the band consisted of Hutchison, his brother Grant (drums), Billy Kennedy ...

, Biffy Clyro

Biffy Clyro are a Scottish rock band that formed in Kilmarnock, East Ayrshire, composed of Simon Neil (guitar, lead vocals), James Johnston (bass, vocals), and Ben Johnston (drums, vocals). Currently signed to 14th Floor Records, they have r ...

, Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

, Travis, KT Tunstall

Kate Victoria "KT" Tunstall (born 23 June 1975) is a Scottish singer-songwriter and musician. She first gained attention with a 2004 live solo performance of her song " Black Horse and the Cherry Tree" on '' Later... with Jools Holland''.

Th ...

, Amy Macdonald

Amy Elizabeth Macdonald (born 25 August 1987) is a Scottish singer-songwriter. In 2007, she released her debut studio album, ''This Is the Life (Amy Macdonald album), This Is the Life'', which respectively produced the singles "Mr. Rock & Roll ...

, Paolo Nutini

Paolo Giovanni Nutini (born 9 January 1987) is a Scottish singer, songwriter and musician from Paisley, Renfrewshire, Paisley. Nutini's debut album, ''These Streets'' (2006), peaked at number three on the UK Albums Chart. Its follow-up, ''Sunny ...

, The View, Idlewild, Shirley Manson

Shirley Ann Manson (born 26 August 1966) is a Scottish musician and actress. She is best known as the lead singer of the American alternative rock band Garbage. Manson gained media attention for her forthright style, rebellious attitude, and di ...

of Garbage, Glasvegas

Glasvegas are a Scottish indie rock band from Glasgow. The band consists of James Allan (vocals), Rab Allan (lead guitar) and Paul Donoghue (bass guitar), with Swedish drummer Jonna Löfgren joining the group in 2010 until her departure in 2020 ...

, We Were Promised Jetpacks

We Were Promised Jetpacks are a Scottish indie rock band originally from Edinburgh, formed in 2003. The band consists of Adam Thompson (vocals, guitar), Sean Smith (bass) and Darren Lackie (drums). Stuart McGachan (keyboards, guitar) was a mem ...

, The Fratellis

The Fratellis are a Scottish rock

Rock most often refers to:

* Rock (geology), a naturally occurring solid aggregate of minerals or mineraloids

* Rock music, a genre of popular music

Rock or Rocks may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

...

, and Twin Atlantic

Twin Atlantic are a Scottish alternative rock band from Glasgow, Scotland. The group currently consists of Sam McTrusty (lead vocals, rhythm guitar), Ross McNae (bass) and Joe Lazarus (drums). Lead guitarist Barry McKenna departed from the b ...

. Scottish extreme metal bands include Man Must Die

Man Must Die is a Scottish technical death metal band from Glasgow, formed in 2002.

History

Man Must Die was formed in May 2002, with John Lee, Alan McFarland, Danny McNab and Joe McGlynn. The band members were known throughout the Scottis ...

and Cerebral Bore. One of the most famous and successful electronic music

Electronic music is a genre of music that employs electronic musical instruments, digital instruments, or circuitry-based music technology in its creation. It includes both music made using electronic and electromechanical means ( electroac ...

producers, Calvin Harris

Adam Richard Wiles (born 17 January 1984), known professionally as Calvin Harris, is a Scottish DJ, record producer, singer, and songwriter who has released six studio albums.

His debut studio album, ''I Created Disco'', was released in June ...

, is also Scottish. The Edinburgh-based group Young Fathers

Young Fathers are a Scottish band based in Edinburgh, Scotland. In 2014, they won the Mercury Prize for their album ''Dead''.

History

Formed in Edinburgh in 2008 by Alloysious Massaquoi, Kayus Bankole and Graham 'G' Hastings, the group starte ...

won the 2014 Mercury Prize for their album Dead

Death is the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain an organism. For organisms with a brain, death can also be defined as the irreversible cessation of functioning of the whole brain, including brainstem, and brain ...

.

Scottish musical acts to achieve international commercial success through the 2010s and 2020s include Susan Boyle, Lewis Capaldi

Lewis Marc Capaldi ( ; born 7 October 1996) is a Scottish singer-songwriter and musician. He was nominated for the Critics' Choice Award at the 2019 Brit Awards. In March 2019, his single "Someone You Loved" topped the UK Singles Chart where ...

, Nina Nesbitt

Nina Nesbitt (born ) is a Scottish singer and songwriter. She has two top 40 singles, and is known for her single "Stay Out", which peaked at No. 21 on the UK Singles Chart in April 2013.

Her first EP, ''The Apple Tree'', was released in Apr ...

and Chvrches

Chvrches (stylised CHVRCHΞS and pronounced "Churches") are a Scottish pop band from Glasgow, formed in September 2011. The band consists of Lauren Mayberry, Iain Cook, Martin Doherty and, unofficially since 2018, Jonny Scott. Mostly deriving f ...

. Susan Boyle achieved international success, particularly with her first two studio albums, topping both the UK Album Charts and the ''Billboard 200'' chart in the United States.

Jazz

Scotland has a strong jazz tradition and has produced many world class musicians since the 1950s, notablyJimmy Deuchar

James Deuchar (26 June 1930 – 9 September 1993) was a Scottish jazz trumpeter and big band arranger, born in Dundee, Scotland. He found fame as a performer and arranger in the 1950s and 1960s. Deuchar was taught trumpet by John Lynch, who lear ...

, Bobby Wellins

Robert Coull Wellins (24 January 1936 – 27 October 2016) was a Scottish tenor saxophonist who collaborated with Stan Tracey on the album '' Jazz Suite Inspired by Dylan Thomas's "Under Milk Wood"'' (1965).

Biography

Robert Coull Wellins was ...

and Joe Temperley

Joe Temperley (20 September 1929 – 11 May 2016) was a Scottish jazz saxophonist. He performed with various instruments, but was most associated with the baritone saxophone, soprano saxophone, and bass clarinet.

Life

Temperley was born in Cowd ...